|

Private Collection

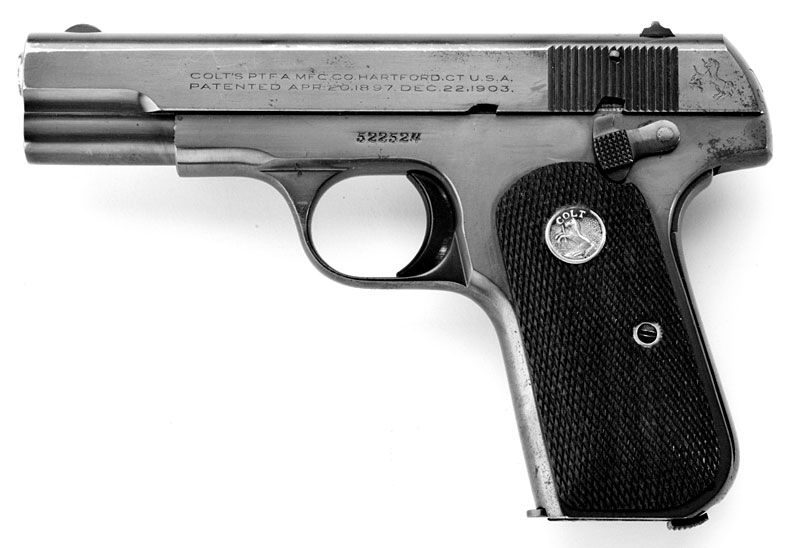

Colt Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless .32 ACP factory

inscribed - serial number 522524, factory

inscribed "Louis Cukela, Captain USMC" with factory

checkered walnut stocks with flush medallions, a one gun

shipment to Capt. Louis Cukela, USMC, Norfolk, Virginia on

January 9, 1937, processed on Colt factory order number

17414/1.

Colt Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless .32 ACP factory

inscribed - close-up of inscription on right side to two time Medal of

Honor recipient Louis Cukela, Captain USMC.

Louis Cukela (May 1, 1888 – March 19, 1956) was a

Croatian-born United States Marine numbered among the

nineteen two-time recipients of the Medal of Honor. Cukela

was awarded the Medal by both the US Army and the US Navy

for the same action during the Battle of Soissons in World

War I. He was also awarded decorations from France, Italy,

and Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

[Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Cukela]

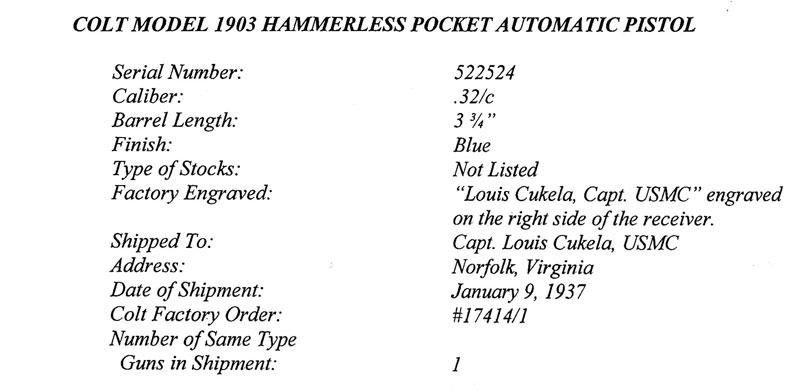

Colt Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless .32 ACP

factory inscribed - factory letter.

Colt Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless .32 ACP

- serial

number 522524, left side.

Captain Louis Cukela, USMC Published

in Leatherneck Magazine, October 2006 by Maj

Allan C. Bevilacqua, USMC (Ret)

Jun 16, 2011 Do you have a dictionary handy?

You do? Good. Pull it down from the shelf and look up the

word eccentric. Don't be surprised if you find a photograph

of Louis Cukela right alongside.

Cukela [pronounced coo-KAY-la] was the living embodiment of

the word, the prime meridian from which any and all things

eccentric are measured, a man who could leave observers

shaking their heads in bewilderment at the same time they

were doubled over in laughter. If there ever was a man who

did things his way, even if that way might have seemed odd,

a man blunt as a bullet and direct as an avalanche, that man

was Louis Cukela. And he always ... always ... had the last

word.

Wait a minute, wait a minute. Who was this Cukela character,

some kind of nut? OK, let's back up and start from the

beginning. Louis Cukela was born in the town of Spalato,

known today as Split, in Croatia in 1888. Maybe that was a

hint of things to come, because Croatia, along with Serbia,

Slovenia and Bosnia, all those feuding, fussing and fighting

places known as the Balkans, was part of what was then known

as Austria-Hungary. That was where in 1914 everything boiled

over and erupted into the First World War, which didn't mean

all that much to Louis Cukela.

He packed up and went to America in 1913. There was a tour

as a cavalry trooper in the U.S. Army that ended in 1916,

but Cukela didn't stay a civilian for long. In January 1917,

just a few months before the United States entered World War

I, he enlisted in the Marine Corps, and in time, found

himself a member of the 66th Company, 1st Battalion, Fifth

Marine Regiment.

In France in 1918, Cukela fought in every battle of the

Marine Brigade, from Belleau Wood to the Meuse River

Crossing. Along the way he collected a commission as a

second lieutenant, as well as the Medal of Honor and four

Silver Star Citations. From the French, there was the Legion

d'Honneur, the Medaille Militaire (the first award of this

prestigious decoration to a Marine officer) and the Croix de

Guerre 1914-18 with two palms and one Silver Star. Italy

decorated him with the Croce al Merito di Guerra, while

Yugoslavia weighed in with the Commander's Cross of the

Royal Order of the Crown of Yugoslavia.

The only award for mangling the English language was

unofficial. Cukela won that hands down when he tore a

careless subordinate a new one, ending with the line that

became famous: "Next time I send damn fool I go myself."

Next time I send damn fool I go myself. Those nine words

swept through General John J. Pershing's American

Expeditionary Forces like Epsom salts through a goose. YANK,

the AEF newspaper, drew a series of cartoons around them.

They found their way into Stateside magazines. The humbler

in the ranks could expect to hear them from his squad

leader. It was rumored that GEN Pershing himself resorted to

them when his patience was sorely tried. And they

established Louis Cukela as a world-class eccentric.

Next time I send damn fool I go myself. Try them yourself

the next time some goof-off fouls things up. see how good it

feels. Kind of takes the strain off the liver.

For Louis Cukela, though, that was just the start. There

were always new challenges, and there were always inventive

ways of overcoming them. And always there was the last word.

Take the case of the School Solution. That was in the 1930s

when Cukela, then a captain, attended the Army's Infantry

School at Fort Benning, Ga. At the finish of one particular

practical application problem in infantry tactics, Cukela

was called upon to present his solution to the situation.

"I attack," was Cukela's response.

That, according to the instructor, was not the proper course

of action given the situation. Examining all the aspects of

the situation in detail, the instructor went on to explain

that the proper course of action, the School Solution, was

to withdraw to more defensible terrain and establish a hasty

defense.

"I am Cukela. I attack," Cukela retorted. Then, tapping the

ribbon of the Medal of Honor above his left breast pocket,

he fired the last word. "How you think I get this?"

Fort Benning may have been the Army's school for infantry

officers, but that didn't rule out the school including

classes in equestrianism-horseback riding. Officers on

horseback were a leftover from the Army's days of chasing

Geronimo across Arizona, but every officer student at Fort

Benning put in a certain amount of hours on top of a horse.

It took Louis Cukela to come up with a unique method of

getting a horse's attention.

Riding a horse might have seemed like duck soup for an old

cavalry trooper. The truth was, though, Cukela didn't like

horses, didn't like them the least little bit. On the other

hand, if the antics of one particular horse can be taken to

mean anything, horses didn't care all that much for Cukela

either.

Anyone watching might have suspected that fact on the day

Cukela's mount took off on him at a gallop. Despite every

command of bridle and bit, the horse lit out for the horizon

with Cukela bouncing up and down in the saddle like a rubber

ball on top of a water fountain. None of the methods that

had been taught persuaded the horse to even slow down, much

less stop. The horse was headed for the Chattahoochee River

and Alabama.

Tossing aside the accepted means of controlling a horse,

Cukela sawed on the reins and shouted, "Stop, horse!" The

horse kept right on going.

"STOP, HORSE!" Louder this time. No response from the horse

except to gallop faster.

"STOP, HORSE!" People in downtown Columbus stopped and

listened, wondering what all the commotion was. The horse

shifted into a higher gear.

Enough was enough. Cukela balled up his fist and slammed it

down squarely on top of the horse's head. The horse

staggered and stumbled to a halt, tossing its head and

staring about with out-of-focus eyes.

Cukela leaped from the saddle, snatched the bridle and

yanked the horse's head down to eye level. "You listen good,

horse," he growled. "I am Cukela. You are horse. I tell you

stop, you stop. You not stop I give you hit break your

head." Cukela turned on his heel and stalked off, leaving

the stunned horse shaking its head. "Stupid horse," Cukela

muttered.

Blunt as a bullet. Direct as an avalanche.

That may have been what the company commander in San Diego

thought when Cukela appeared as a member of the Adjutant and

Inspector's official party. The Adjutant and Inspector was

the forerunner of today's Inspector General. Then as now,

the Adjutant and Inspector represented the Commandant of the

Marine Corps, and Marine Corps commands could expect to

stand A&I Inspections on a regular basis.

That was what was taking place when Capt Cukela found a

number of glaring irregularities in certain records, records

not maintained in the manner stipulated by the Marine Corps

Manual. Asking for the company's copy of the Marine Corps

Manual, Cukela thumbed through it to the appropriate

passages.

Then, ripping out the particular pages, Cukela handed them

to the company commander. "Here, you not needing these pages

anymore. You have better way, hah?"

Have you ever, when you were firing the rifle range, been

ordered to fix bayonets and charge? You might have if you

had been a recruit at Parris Island in the late 1930s. That

was when, during a particularly bad string of rapid fire,

the range officer, Capt Cukela, snatched the microphone from

his line noncommissioned officer.

"Cease fire. Clear and lock your piece. Fix bayonets. Charge

the butts!" Cukela bellowed. Fifty bewildered recruits went

galumphing downrange with fixed bayonets while Cukela urged

them on. "You can't shoot them; you go stab them."

The Golden Age of Cukela had to have been at Norfolk, Va.

Retired just prior to the outbreak of WW II, then-Major

Cukela was almost immediately recalled to active duty and

assigned as Commanding Officer, Marine Barracks, Norfolk

Naval Base. Long years after he left, Marines at Norfolk

were still telling Cukela stories.

One particular story that lived on grew out of Cukela's

penchant for leadership by walking around. He didn't believe

in leading from behind a desk; he believed in getting out

and seeing first-hand what was going on every day. Not a bad

style, come to think of it.

It happened that as Cukela was ascending the ladder to the

second deck of the barracks, two young Marines, new hands,

were coming down. As they had been taught in boot camp, they

stood aside at attention, allowing the major to pass.

Instead, he stopped.

Skewering one of the Marines with a piercing gaze, he asked,

"You know who I am?"

"No, sir," replied the puzzled Marine.

"Hmph," snorted Cukela. "Dumb. Don't know nothing."

Turning to the other Marine, Cukela asked the same question.

"You know who I am?"

"Yes, sir," the Marine responded smartly. "You're Major

Cukela."

"Hmph." Another snort. "Wise guy. Think you know

everything." That last word again.

As to getting out and about, well, Cukela did that by

bicycle. There was a war on. A lot of things were in short

supply. There was rationing, and not the least of the

commodities rationed was gasoline. As a means of conserving

fuel, Cukela got about the base on a bicycle, a conveyance

not without its perils.

Do you remember the old taunt when you were a kid playing

sandlot baseball and muffed an easy ground ball: "Two hands

for beginners"? Riding a bicycle was strictly a two-hands

job for Cukela. Any attempt to guide a bicycle with only one

hand was a surefire preliminary to Cukela and the bicycle

both ending up in a heap.

As a result, there was a standing instruction that Maj

Cukela was not to be saluted when he was on a bicycle. That

was, of course, a challenge no Marine could resist. Marines

were known to go out of their way to search out Cukela when

he was mounted on his bicycle. Then it was a matter of

rendering the proper courtesy, a hand salute.

For any officer, and for Cukela in particular, a salute was

a courtesy that was to be returned. He never failed to do

so. He never failed either, to go tumbling rump over

teakettle to land in a heap, much to the secret delight of

the Marine who had brought the whole mishap about. But it

was Cukela as usual who always had the last word.

"How many times I got to tell you, don't salute when I'm on

the bicycle?"

Louis Cukela, a real funny guy. But a mighty warrior and

stand-up guy who always looked out for his Marines, and who

could always be counted on to be there when a Marine needed

a helping hand. [Source:

https://www.mca-marines.org/mcaf-blog/2011/06/16/next-time-i-send-damn-fool-i-go-myself] |